Tags

Art, Authors, Books, Creativity, Ernest Hemingway, Literary Places, Paris, Reading, Wives, Writing

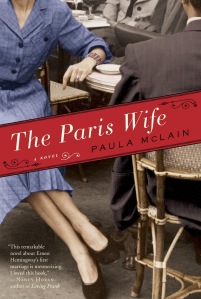

Regular readers of Persephone Writes will already know about my literary obsession with Paris. So it shouldn’t surprise anyone when I say that I absolutely loved The Paris Wife, by Paula McClain, our second book pick for the Literary Wives series. It is one of the best books I’ve read in quite some time: the story is riveting and absorbing, and the book is a brilliant study in craft. It’s a tour de force, an epic love story as well as a trip back to one of the most romantic literary periods in history.

Regular readers of Persephone Writes will already know about my literary obsession with Paris. So it shouldn’t surprise anyone when I say that I absolutely loved The Paris Wife, by Paula McClain, our second book pick for the Literary Wives series. It is one of the best books I’ve read in quite some time: the story is riveting and absorbing, and the book is a brilliant study in craft. It’s a tour de force, an epic love story as well as a trip back to one of the most romantic literary periods in history.

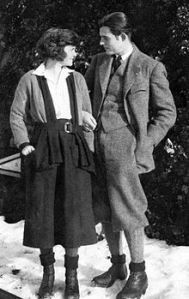

The novel is based on the real-life love affair and marriage of Ernest Hemingway and Hadley Richardson. As the title of the book implies, there is more than one wife: Hem was married four times, and Hadley was his first wife – the Paris wife. The couple spent the better part of their five year marriage in Paris among the many literary expatriates who flocked there in the late 1920s. As you might expect, the book is peopled with writers: Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Sherwood Anderson, Sylvia Beach, Ezra Pound, Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald, and others, all deftly and brilliantly brought to life under McClain’s pen.

Hadley is an emotionally wounded and directionless 28-year-old when she meets the much younger, attractive, and ambitious Hemingway at a party. The two begin an intense courtship, against the advice of well-meaning friends, and ultimately marry. After a short impoverished stint with Ernest working as a journalist in Chicago, they risk everything and move to Paris, where they’ve been told by Anderson the writing world is “happening.” Something about Ernest brings out another side of Hadley, one less cautious and reserved, one more willing to take the chances necessary to live and experience life rather than to simply exist as an observer on the fringes. Hadley brings out Ernest’s vulnerable side. He feels safe with her and empowered to be the writer he knows he can be. The two enter Paris unprepared for the challenges and temptations that await them, eventually forcing them to make the most important, difficult, and painful decision of their lives.

The theme of choice is prominent throughout the novel. From the beginning, it is clear  that Hadley chooses Ernest and everything about him and the life they will lead. She makes this choice again and again, resolutely, throughout the novel even as circumstances and personalities change. Love isn’t portrayed here as something neat and tidy. Hadley and Ernest’s romance is messy and painful, but attractive and sustaining, as well. It is clear that one of the traits Hadley best exhibits as a wife is her understanding that for marriage to survive, each spouse must at some time or another, or even very often, CHOOSE to continue on in the relationship, choose to continue to try and make things work, choose to love. Unfortunately, sometimes one or the other spouse is incapable or unwilling to make the choice. Hadley is not blind. She makes her choice with her eyes open, albeit often unable to see clearly what is around the next bend. She has a maturity and a wisdom that few others in their world possess and it is this that sets the Hemingways apart from their social-literary set, both in Paris and around Europe. It is clear that Hadley’s choice to continue on with Ernest hurts her. But she persists in hope, confident that whatever else happens between them, she truly loves him. It is this aspect of her character that I admired the most, especially as I approach the 20-year anniversary in two weeks of my own marriage. Hadley has the stick-to-itiveness that marriage needs if it is going to survive, and in our own current climate, when so many marriages fail to make it even to the three-year mark, her example is one to be emulated.

that Hadley chooses Ernest and everything about him and the life they will lead. She makes this choice again and again, resolutely, throughout the novel even as circumstances and personalities change. Love isn’t portrayed here as something neat and tidy. Hadley and Ernest’s romance is messy and painful, but attractive and sustaining, as well. It is clear that one of the traits Hadley best exhibits as a wife is her understanding that for marriage to survive, each spouse must at some time or another, or even very often, CHOOSE to continue on in the relationship, choose to continue to try and make things work, choose to love. Unfortunately, sometimes one or the other spouse is incapable or unwilling to make the choice. Hadley is not blind. She makes her choice with her eyes open, albeit often unable to see clearly what is around the next bend. She has a maturity and a wisdom that few others in their world possess and it is this that sets the Hemingways apart from their social-literary set, both in Paris and around Europe. It is clear that Hadley’s choice to continue on with Ernest hurts her. But she persists in hope, confident that whatever else happens between them, she truly loves him. It is this aspect of her character that I admired the most, especially as I approach the 20-year anniversary in two weeks of my own marriage. Hadley has the stick-to-itiveness that marriage needs if it is going to survive, and in our own current climate, when so many marriages fail to make it even to the three-year mark, her example is one to be emulated.

Hadley’s clarity of intention is much of what keeps the novel moving forward. By all accounts, Hemingway was not an easy man to be married to. He seems to see his wife of the moment, and the wives subsequent, as necessary muses. They function as support for his ego when he can’t muster the will to do it on his own. And yet these strong women, Hadley being the first among four, for some reason subsume their own deeply creative aspirations and talents in order to nurture Ernest’s gifts. Hadley is an exceptional pianist, and yet she sets her passion aside and even doubts her own talent, becoming more deeply embroiled in the literate swirl of the Parisian expat set, committing herself instead to supporting and nurturing Ernest. The obvious problem here is that, over time, a woman in this scenario becomes half a self — regardless of how much she is living the rest of her life to the fullest, the denial of her creative spirit and unique gifts has profound psychological ramifications. Hadley clearly struggles with this unhealthy tension throughout the book and it is unfortunate that Ernest sees the truth of her as a whole person so dimly that he fails to support her efforts until it is too late.

It would have been easy for Hadley to become spiteful and vindictive with all she has to put up with. Her dogged persistence continues even when her consistent effort might be the thing that is really doing herself the most harm. One of the things the wife in this novel has to learn is that love cannot be forced or manipulated. An interesting lesson for a woman who seems to be fully cognizant of the truth that love is a choice.

It is clear that McClain’s intention in allowing Hadley to tell the story from her perspective is to give the reader a glimpse into a little explored room in Hemingway’s faceted life. Hadley “knew him when” – before he achieved the canonical status he would later command. And yet, Hadley never figured in his work. It is as though she moves through the back rooms of their life together as a grey ghost: silent, clearly present, but unacknowledged. And yet, were it not for her strength and her resilient belief in Ernest, he might never have become the writer he eventually became. The tension caused by his unwilling realization of this fact drives his choices. It is as if he both knows and refuses to accept his reliance on Hadley and makes choices that will deliberately liberate him from his reliance and thus give him the illusion of competent solitary self-reliance. This is hard to read about, because it is so incredibly self-destructive and so damaging to Hadley. Yet she emerges, in my opinion, as the stronger of the two. Perhaps this is because she never veers from the truth and she can look back and say that she has no regrets, that she did all she could. Her conscience is clear and she ultimately achieves a wholeness Ernest is not capable of.

McClain allows Hadley’s story to be told from her perspective, with an honesty and candor that is particularly touching and very refreshing after American Wife, last month’s Literary Wives choice. Hadley doesn’t try to hide her flaws or Ernest’s. She simply tells the story. I never felt the need to question her reliability. Neither did I question her repetitive choice to stay and love and work the marriage through its ups and downs. Her experience of being a wife in the novel was an experience I could relate to on many levels. When she married, she committed her life to Ernest and she made sure she did what she could to honor and live up to that commitment, even when it was excruciatingly painful.

Ernest did finally, at the end of his life, write about his time with Hadley in Paris and it was this book, A Moveable Feast, which inspired McClain to find out more about the woman who had been so clearly dear to the great writer. The Paris Wife is McClain’s way of trying to give voice and substance to this wife who stood by her man to the end. Hadley clearly believed the risk of loving Hemingway was something she could not live without and she was a better, more whole person for loving him. This comes through so beautifully in the novel and reminds us that love exacts a price from us. In order to love truly, we must agree to submit ourselves to the crucible and to be changed by the experience. Love can hurt, love can devastate. It can also elevate and raise one to sublime heights. But it always changes one, and that is the true risk. Hadley chooses to take this risk not once but many times and seems to come to the conclusion that if she had to do it all over again, she wouldn’t hesitate to choose the same.

Do whatever you have to do to get this book on your nightstand or into your beach tote. It’s romantic, dreamy, and brilliantly told. Plus, who wouldn’t jump at the chance to travel back in time to jazz-age Paris, even if it is only via the arm (or beach) chair?

If you’ve already read The Paris Wife, I’d love to hear your thoughts on the book. Also, don’t forget to stop by The Bookshelf of Emily J., One Little Library, and Unabridged Chick to see what my Literary Wives co-hosts thought of this month’s pick. Our next title is A Reliable Wife, by Robert Goolrick. Are you in? 🙂

Here are a few tunes that, for me, recall themes and moods of The Paris Wife. Enjoy!

“Jai un message pour toi,” by Josephine Baker, because it sounds like the cafe beneath Hadley and Ernest’s Paris apartment.

“Azure-te,” by Nat King Cole, because Hadley surely has the Paris blues at the outset of the Hemingway’s journey, and then on and off throughout the novel, for all of the reasons he sings about.

“C’est Magnifique,” by Lucienne Delyle, because being in love in Paris can be spectacular, but it can also be painful.

“J’ai deux amour,” by Madeleine Peyroux, because…well…..Hadley is the Paris wife.

“La Vie en Rose,” by Edith Piaf, because it is the essence of Paris.

I love Edith Piaf! What a nice idea to include some of the music of that age. I love what you say about choice and love, especially since I saw Hadley as more subsumed and swallowed up. I even claimed that she gave up her agency to support Ernest, but perhaps she was really just choosing. The unfortunate part is that he did not reciprocate. It was so hard to read about her strength and maturity and to see how Ernest just disregarded her and followed his lust rather than his logic and choosing his love. Nice review, Angela!

LikeLike

I’m so glad you liked the music, Emily! 🙂

Sometimes people choose to be subsumed….perhaps that is part of the choice Hadley makes. But I think people need to take responsibility, ultimately, for their choices. To choose to stay in a marriage that is abusive or toxic or flagrantly adulterous isn’t ever a good choice. I like that Hadley continues to hope that Ernest will change. But it seems like in the end, she realizes he not only will not, but that he can not — perhaps because he is first wedded to his work, as you and Ariel point out. Ultimately, this first invader in the marriage is the real problem. He wants to be married to his work first, and even though she tried to accept this and “let him be” it still wasn’t enough for him. I don’t think any woman would have been able to be the kind of wife he wanted, but I think Hadley was the kind of wife he needed, because she truly did accept him, warts and all, as he was.

LikeLike

I couldn’t agree more! I love the music, too! I rented Midnight in Paris to watch tonight as well. I wish I’d had time to watch it before the review, but oh well.

I love your point about choosing the marriage. That is so true. And the marriage only works if both partners continue to keep choosing the marriage. Obviously, that didn’t happen for Ernest and Hadley, but congratulations on your own long marriage!

I was confused and hurt right along with Hadley that she was never featured in any of his books. But I think you’re right—even though she soon ceased to be his muse, she continued to be the wife he needed. She did choose to be subsumed, for the sake of his work, and it did succeed in making him one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century. Ultimately, though, I think he is more to be pitied. He achieved his greatest ambition, and yet his life was clearly not happy.

LikeLike

Midnight in Paris is so much fun — what a romp! That is the perfect film to watch to accompany this book! 🙂

I agree with you about Hemingway. He seems to be such a tragic figure. It is sad that his experiences didn’t seem to change him, that he never grew to appreciate the love he received, but simply felt compelled to reject and destroy it. I wonder if some people are psychologically incapable of changing, or whether it is always a choice?

Thank you, Ariel, for stopping by and leaving something thoughtful behind. 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: Literary Wives Part Two: The Paris Wife | One Little Library

Great review! There are so many books about Americans in Paris, not all of which are worthy, but thanks to your review i know this one is worthwhile. I’ve added it to my list!

LikeLike

That means a lot coming from you, Emily! With your experience of Paris, and based on the things I’ve seen on your blog about your time there, I don’t think you could help but be enchanted by this book. The love story is by turns charming and painful, but the view of Paris in the jazz-age is spot on, and McClain simply nails the personalities — they all come to life! I have an extra copy of the book and I’d be happy to send it to you. Email me if you want. I’m so happy you stopped by and thank you for your appreciation. 🙂

LikeLike

Angela that is so sweet of you and beyond generous! I will take you up on the offer and email you 🙂

LikeLike

Wonderful! I’m so glad. And you’ll have to let me know what you think after you’ve had a chance to read it.

LikeLike

Such a wonderful review Angela – thank you. You highlight so well the complexity of love and surrender and sacrifice. It is often hard to find the right balance. It is so easy, particularly for us women I think, to become ‘lost’ as we have that tendency to give too much. I think it’s something that needs ongoing re-evaluation when in a relationship as it is so easy to slip past the point of sacrifice and compromise and become little more than a doormat. I really never like, though, how others ‘judge’ women who choose to give, what they consider to be, too much. It is always for the individual. I only ever hope that a person gives from a point of choice rather than lack of self-esteem and having codependency issues. Such a thoughtful and thought provoking review. Your music choices were just lovely too. Take good care and congratulations on your upcoming 20 years. I think this is a beautiful achievement. 🙂

LikeLike

Yes, balance…..so essential but so difficult. You are absolutely right, Ruth. And why is it that this is harder for women? One of the things I realize n these last two novels is that the women really struggle with this to be authentic and whole while still function in relationship. I like what you say about not judging others. This is hard, but we se only what is on the outside. No one can ever know what really goes on in a marriage, ever, except the two people within it and God. And often, even those two people perceive the same things entirely differently, and there are lots of misunderstandings and miscommunications. Conscious decision to give is the ideal, but it seems to me that more often or very often, codependency and lack of self-esteem dictate. Do you find that in your work with people and your research?

Thank you for your appreciation and your good wishes — I always love the comments you take the time to leave. Have a great week. I’ll be in touch. 🙂

LikeLike

I certainly see less conscious choice generally Angela and I’ve seen a lot specifically. I think that authenticity is one of our biggest challenges (I’m just writing an article on it!) and even more so for women. I fear that lack of self-esteem and feelings of deep unworthiness often dictate much more than conscious choices coming from a place of inner strength. It’s very sad I think. I so enjoy commenting on your posts! 🙂

LikeLike

Ruth, this is a subject I feel very strongly about and I will be looking forward to reading your article when its finished. I’m so glad you are writing it — it’s a subject that needs to be addressed, a subject people need support and guidance in.

LikeLike

You won’t be surprised to know that I completely agree with you Angela! 🙂

LikeLike

🙂 Thanks, Ruth.

I know your reading list is already long enough to last the rest of your life, but I really do think you’d like this novel, if you ever see your way clear to picking it up.

LikeLike

I will put it on my list Angela – I cannot resist! 🙂

LikeLike

My review: 2013/06/the-paris-wife-by-paula-mclain.html?m=1

I really like your emphasis on Hadley choosing to devote herself to Ernest. There were so many times she was suspicious, but she chose to trust him. I like your comments about love not always being pretty. And the music! Thanks for that! I LOVE Nat! Kinda forgot he went back that far! This was not one of my favorite books, but quite interesting and informative. I want to read A Moveable Feast now, as well as some of Hemingway’s other works. One thing I neglected to mention in my own review, but it struck me as humorous and rather cute, was their emphasis on nicknames. It reminded me of my sons and their friends, always using nicknames for each other.

LikeLike

Hi Lynne! So glad you stopped by and thank you for your kind comments on my review. I’m happy to hear you liked the music — that was fun. I also wanted to read A Moveable Feast after finishing the book, so I ordered it. The table of contents really makes it pretty clear how closely McClain followed the couples’ experiences in Paris. It looks wonderful and I can’t wait to read it. If you do, I’d love to hear what you think of it. It’s funny you mention the nicknames — I decided yesterday morning that if I ever get another cat, I’ll name her Hadley. 🙂 Cheers! And thanks so much for stopping by!

LikeLike

Pingback: Review: The Paris Wife by Paula McLain | Books are my Bling

Pingback: Literary Wives Wrap-up: Raising the Question of Larger Significance | Persephone Writes

Pingback: Review: The Paris Wife | Ciara Reads Books